Most Thursday mornings, you’ll find five elderly veterans at a corner booth of the Bell Tower Cafe in Los Altos, California. They met by happenstance over the years, discovering that their group had one representative from each of the five branches of the U.S. military. They had served at different times and in different locations around the world, but all wound up retiring in Northern California. Mike Crisp, who served as a Coast Guard officer in Hawaii in the 1960s, recently got to thinking about what military experiences they might have in common. The following Thursday, he presented each of them with a can of SPAM.

The gift got a laugh from the group and a lady at a nearby table took a picture of the five men posing with their cans of SPAM. Taste and smell are remarkable conduits to memory, and these veterans know that a bite of SPAM can transport them back in time. Memory is what these Thursday mornings are all about.

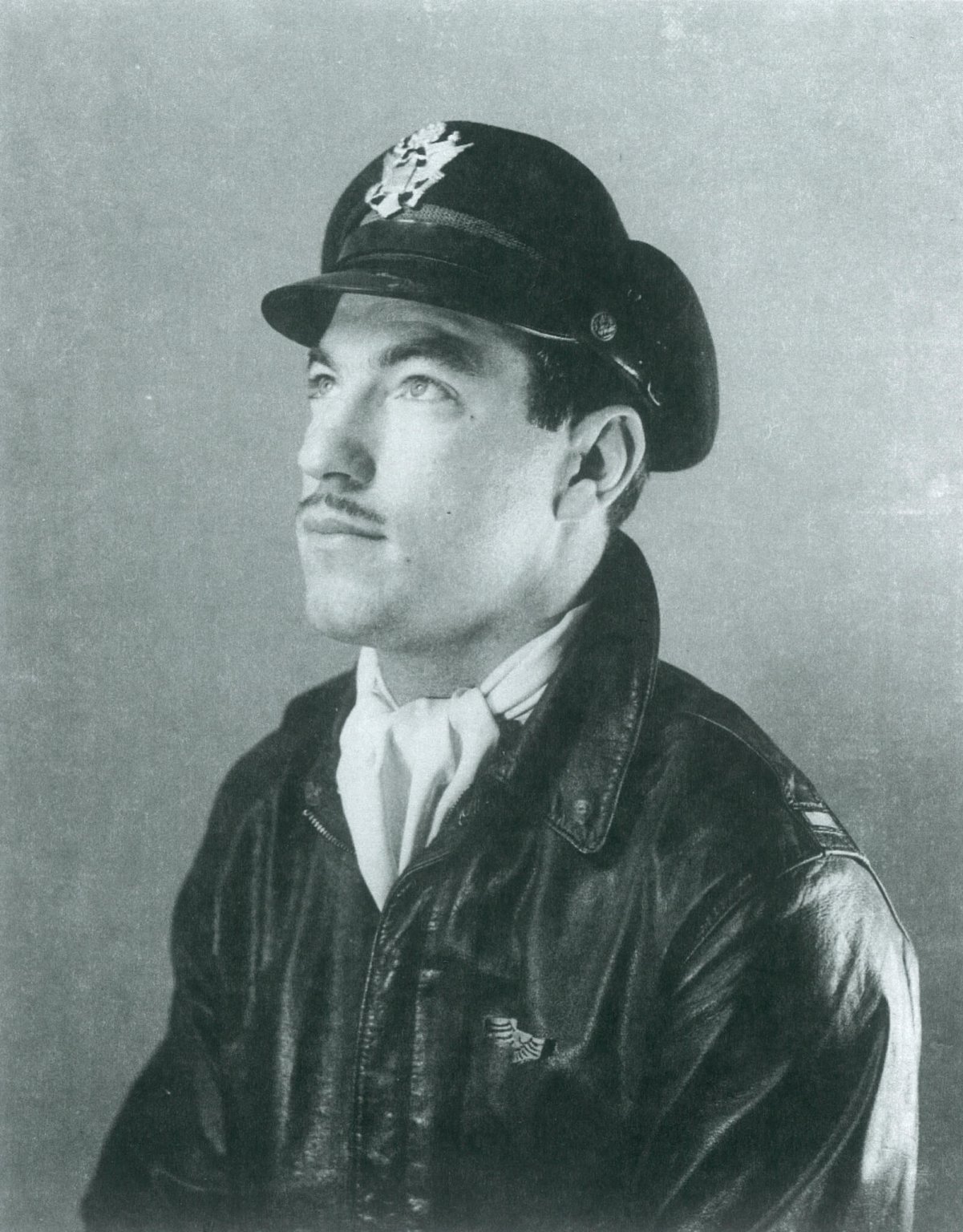

Of the five men at the table, one is acknowledged as the “celebrity” and the one with the best stories to tell about his service: Chuck Baker, who at age 101 is a couple of decades older than his fellow vets. Baker piloted B-17 bombing missions over Germany in the spring and summer of 1944, when he was just 25 years old.

Fit and clear-eyed, Baker doesn’t hear so well anymore—the long-term effects of the twin .50 caliber machine guns that blasted away just above the cockpit in his B-17. Nonetheless, on his hundredth birthday last year, he tried something he had managed to avoid during his Army days: parachuting out of an airplane. Flying B-17s for the Army Air Corps was one of the most dangerous postings in all of the armed forces; on a single mission he might have a one-in-ten chance of being shot down. Baker was initially told he would have to fly twenty-five missions, the odds of surviving all of which were no better than the flip of a coin. As he approached that milestone, he learned that thirty missions were required of him instead. Later that number was upped again, to thirty-five. All in all, it’s less surprising that Baker made it to 101 than it is that he lived to 26.

Every time Baker retells a story, though, his fellow veterans ask a few questions that reveal a new detail or two.

“Did the formations change elevation when the flak started?” asks Donn Bryne, a Naval aviator who flew P-3 surveillance aircraft during the Vietnam War.

“Would planes in the lower formation be more vulnerable to being hit by German guns?” wonders Justin Berglund, a former Marine.

The men sip their coffee as Baker reaches back in his memory for the details. The planes, he says, had to stay in tight formation to guard against enemy fighters, so changing altitude wasn’t possible. As the pilot, he could only watch as the guns adjusted for elevation with each firing.

“There were four guns attached to a radar aimer,” he explains. “So you’d see four bursts: boom, boom, boom, boom. As you were approaching the target you’d see them zeroing in on your elevation. You just knew that one had your name on it.”

“I’m sure everyone up there, when they got into difficulties, had some kind of talisman,” recalls Baker. “A rabbit’s foot or a picture of their girlfriend. I resorted to the Holy Bible.” It was Psalm 23 that he would recite when he flew into flak. He begins to recite it now: “Though I walk through the valley of death…” There’s a hitch in his voice and his eyes tear up. For a moment, the table is quiet.

It’s often the little details that bring Baker’s memories of his days as a B-17 pilot to life. He remembers the bitter cold of 25,000 feet in an unpressurized and unheated aircraft—temperatures could dip to –60°F, and frostbite was common. He also remembers the generous glass of single-malt Scotch and the warm bath with which he celebrated each completed mission.

“Did you fly missions on D-Day?” Byrne asks. It’s a personal question: Byrne’s own father was part of the second wave onto Omaha Beach that day. Baker says he did fly his B-17 in support of that invasion, bombing rail lines to frustrate the German counterattack. “All the men in my crew got to look down at the invasion boats in the channel,” he recalls. “But I was flying in tight formation so I had to keep an eye on the planes next to me.”

Although he can still remember the fear he felt and mourns the friends he lost, Chuck also remembers the exhilaration of that time. He was a young man on an adventure. “That experience was the most fascinating of my life,” he says. “I didn’t like to be shot at, of course. But the camaraderie, the education I received flying those big airplanes, I wouldn’t have missed it for anything.”

Code of Honor

It doesn’t take long in the company of these five men to realize that what they have in common goes far beyond eating SPAM during their military days. These are men who talk unironically about honor, who share a belief in the value of service to their country. For the younger veterans, the example set by Baker’s generation was the reason they were drawn to serve when their time came.

“There was only one greatest generation,” says Crisp. “You know, I admire those guys so much.”

“We looked up to men like Chuck—these were our heroes,” agrees Byrne. “During World War II, everybody had a son, daughter, cousin, or neighbor who was involved in the war effort. There was a clear sense of being together and unified as a nation.”

At their corner table, these five veterans have often discussed whether that feeling of national unity is still possible. What sort of challenge, they have wondered, would it take to bring us together with the spirit they remember during the world war?

Chuck Baker flying over San Fransisco

At the beginning of 2020, that question was suddenly on everyone’s minds. Not long after a film crew from Hormel Foods visited the Bell Tower Cafe to meet Baker and his friends, the group had to suspend their weekly meetings because of the arrival of COVID-19. Their plan for a group parachuting adventure to celebrate Baker’s 101st birthday also had to be postponed. The country they served was suddenly relearning what these veterans know from personal experience: Times of sacrifice and hardship are the very times that bond great nations together.